Products of graphs¶

This module gathers everything related to graph products. At the moment it contains an implementation of a recognition algorithm for graphs that can be written as a Cartesian product of smaller ones.

References:

Author:

- Nathann Cohen (May 2012 – coded while watching the election of Francois Hollande on TV)

Cartesian product of graphs – the recognition problem¶

First, a definition:

Definition The Cartesian product of two graphs G and H, denoted G◻H, is a graph defined on the pairs (g,h)∈V(G)×V(H).

Two elements (g,h),(g′,h′)∈V(G◻H) are adjacent in G◻H if and only if :

- g=g′ and hh′∈H; or

- h=h′ and gg′∈G

Two remarks follow :

- The Cartesian product is commutative

- Any edge uv of a graph G1◻⋯◻Gk can be given a color i corresponding to the unique index i such that ui and vi differ.

The problem that is of interest to us in the present module is the following:

Recognition problem Given a graph G, can we guess whether there exist graphs G1,...,Gk such that G=G1◻⋯◻Gk ?

This problem can actually be solved, and the resulting factorization is unique. What is explained below can be found in the book Handbook of Product Graphs [HIK11].

Everything is actually based on simple observations. Given a graph G, finding out whether G can be written as the product of several graphs can be attempted by trying to color its edges according to some rules. Indeed, if we are to color the edges of G in such a way that each color class represents a factor of G, we must ensure several things.

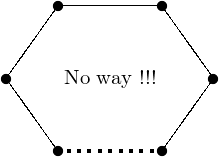

Remark 1 In any cycle of G no color can appear exactly once.

Indeed, if only one edge uv of a cycle were labelled with color i, it would mean that:

- The only difference between u and v lies in their i th coordinate

- It is possible to go from u to v by changing only coordinates different from the i th

A contradiction indeed.

That means that, for instance, the edges of a triangle necessarily have the same color.

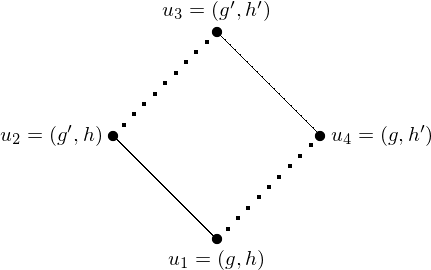

Remark 2 If two consecutive edges u1u2 and u2u3 have different colors, there necessarily exists a unique vertex u4 different from u2 and incident to both u1 and u3.

In this situation, opposed edges necessarily have the same colors because of the previous remark.

1st criterion : As a corollary, we know that:

- If two vertices u,v have a unique common neighbor x, then ux and xv have the same color.

- If two vertices u,v have more that two common neighbors x1,...,xk then all edges between the xi and the vertices of u,v have the same color. This is also a consequence of the first remark.

2nd criterion : if two edges uv and u′v′ of the product graph G◻H are such that d(u,u′)+d(v,v′)≠d(u,v′)+d(v,u′) then the two edges uv and u′v′ necessarily have the same color.

This is a consequence of the fact that for any two vertices u,v of G◻H (where u=(uG,uH) and v=(vG,vH)), we have d(u,v)=dG(uG,vG)+dH(uH,vH). Indeed, a shortest path from u to v in G◻H contains the information of a shortest path from uG to vG in G, and a shortest path from uH to vH in H.

The algorithm¶

The previous remarks tell us that some edges are in some way equivalent to some others, i.e. that their colors are equal. In order to compute the coloring we are looking for, we therefore build a graph on the edges of a graph G, linking two edges whenever they are found to be equivalent according to the previous remarks.

All that is left to do is to compute the connected components of this new graph, as each of them representing the edges of a factor. Of course, only one connected component indicates that the graph has no factorization.

Then again, please refer to [HIK11] for any technical question.

To Do¶

This implementation is made at Python level, and some parts of the algorithm

could be rewritten in Cython to save time. Especially when enumerating all pairs

of edges and computing their distances. This can easily be done in C with the

functions from the sage.graphs.distances_all_pairs module.

Methods¶

-

sage.graphs.graph_decompositions.graph_products.is_cartesian_product(g, certificate=False, relabeling=False)¶ Test whether the graph is a Cartesian product.

INPUT:

certificate– boolean (default:False); ifcertificate = False(default) the method only returnsTrueorFalseanswers. Ifcertificate = True, theTrueanswers are replaced by the list of the factors of the graph.relabeling– boolean (default:False); ifrelabeling = True(impliescertificate = True), the method also returns a dictionary associating to each vertex its natural coordinates as a vertex of a product graph. If g is not a Cartesian product,Noneis returned instead.

See also

sage.graphs.generic_graph.GenericGraph.cartesian_product()graph_products– a module on graph products.

Note

This algorithm may run faster whenever the graph’s vertices are integers (see

relabel()). Give it a try if it is too slow !EXAMPLES:

The Petersen graph is prime:

sage: from sage.graphs.graph_decompositions.graph_products import is_cartesian_product sage: g = graphs.PetersenGraph() sage: is_cartesian_product(g) False

A 2d grid is the product of paths:

sage: g = graphs.Grid2dGraph(5,5) sage: p1, p2 = is_cartesian_product(g, certificate = True) sage: p1.is_isomorphic(graphs.PathGraph(5)) True sage: p2.is_isomorphic(graphs.PathGraph(5)) True

Forgetting the graph’s labels, then finding them back:

sage: g.relabel() sage: b,D = g.is_cartesian_product(g, relabeling=True) sage: b True sage: D # random isomorphism {0: (20, 0), 1: (20, 1), 2: (20, 2), 3: (20, 3), 4: (20, 4), 5: (15, 0), 6: (15, 1), 7: (15, 2), 8: (15, 3), 9: (15, 4), 10: (10, 0), 11: (10, 1), 12: (10, 2), 13: (10, 3), 14: (10, 4), 15: (5, 0), 16: (5, 1), 17: (5, 2), 18: (5, 3), 19: (5, 4), 20: (0, 0), 21: (0, 1), 22: (0, 2), 23: (0, 3), 24: (0, 4)}

And of course, we find the factors back when we build a graph from a product:

sage: g = graphs.PetersenGraph().cartesian_product(graphs.CycleGraph(3)) sage: g1, g2 = is_cartesian_product(g, certificate = True) sage: any( x.is_isomorphic(graphs.PetersenGraph()) for x in [g1,g2]) True sage: any( x.is_isomorphic(graphs.CycleGraph(3)) for x in [g1,g2]) True