Introductory Sage Tutorial¶

This Sage document is the first in a series of tutorials developed for the MAA PREP Workshop “Sage: Using Open-Source Mathematics Software with Undergraduates” (funding provided by NSF DUE 0817071). It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license (CC BY-SA).

If you are unsure how to log on to a Sage server, start using a local installation, or to create a new worksheet, you might find the prelude on logging in helpful.

Otherwise, you can continue with this tutorial, which has the following sections:

- Evaluating Sage Commands

- See Evaluating in the Jupyter notebook for the Jupyter notebook

- See Evaluating in the SageNB notebook for the legacy Sage notebook

- Functions in Sage

- Help inside Sage

- Annotating with Sage

- See Jupyter Annotation for the Jupyter notebook

- See SageNB Annotation for the legacy Sage notebook

This tutorial only introduces the most basic level of functionality. Later tutorials address topics such as calculus, advanced plotting, and a wide variety of specific mathematical topics.

Evaluating Sage Commands¶

Or, How do I get Sage to do some math?

We have two parallel subsections here which cover (roughly) the same content.

- See Evaluating in the Jupyter notebook for the Jupyter notebook

- See Evaluating in the SageNB notebook for the legacy Sage notebook

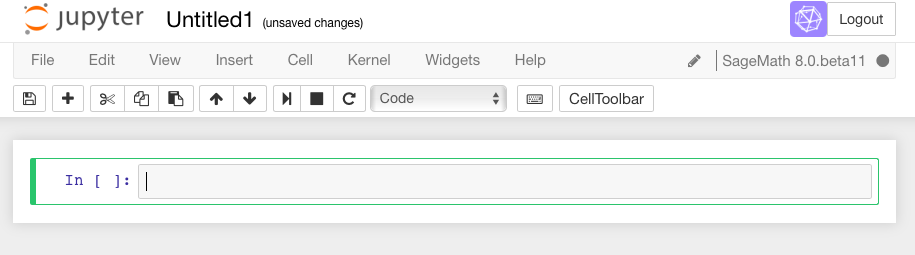

Evaluating in the Jupyter notebook¶

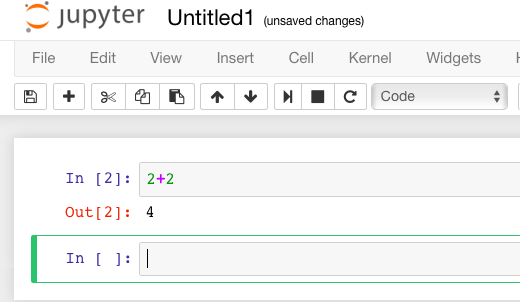

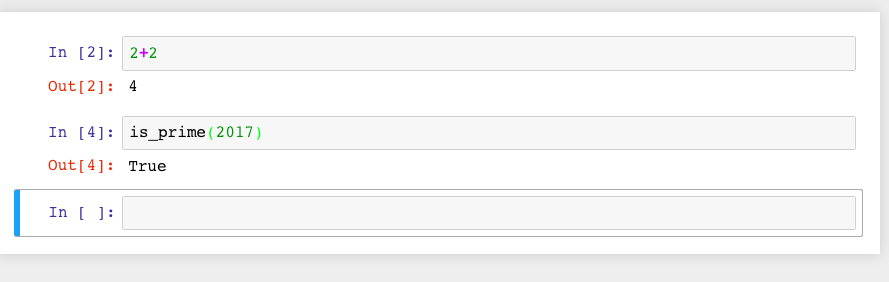

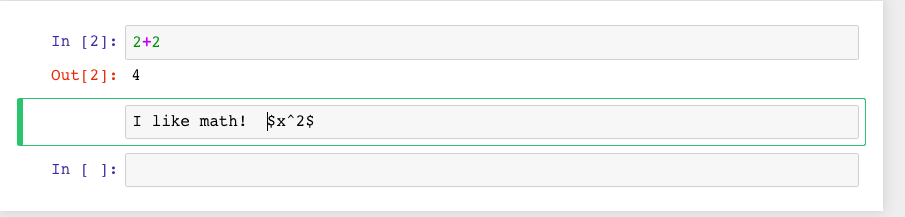

In a Jupyter worksheet, there are little boxes called input cells or code cells. They should be about the width of your browser.

To do math in a Jupyter cell, one must do two things.

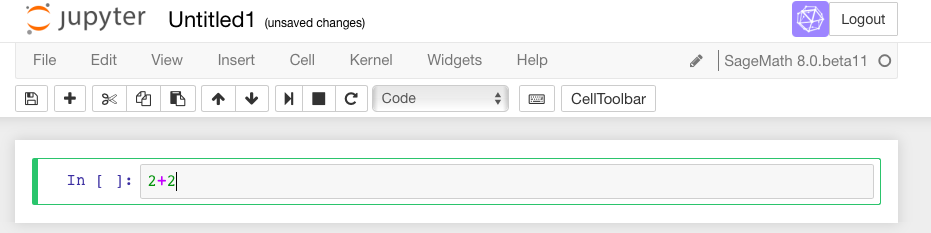

- First, click inside the cell so that the cell is active (i.e., has a bright green border). This was already the case in the first cell above. (If it is blue, the Jupyter notebook is in “command mode”). Type some math in it.

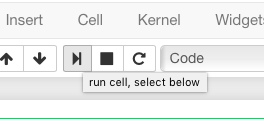

Then, there are two options. A not-very-evident icon that looks like the “play” symbol on a recording device can be clicked:

Or one can use the keyboard shortcut of holding down the Shift key while you press the Enter key. We call this “Shift-Enter”.

Sage prints out its response just below the cell (that’s the 4

below, so Sage confirms that \(2+2=4\)). Note also that Sage has

automatically made a new cell, and made it active, after you evaluated

your first cell.

To do more mathematics, just do the same thing with more cells!

Unlike in the SageNB, one has to learn a variety of keyboard shortcuts or click on various menu items to manipulate cells. There is a help menu to get you started on this; the Jupyter developers also maintain an example notebook which may assist you.

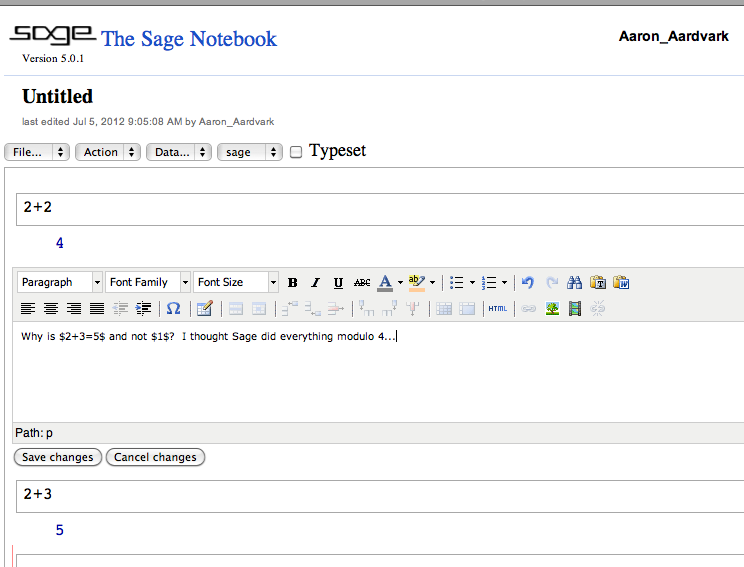

Evaluating in the SageNB notebook¶

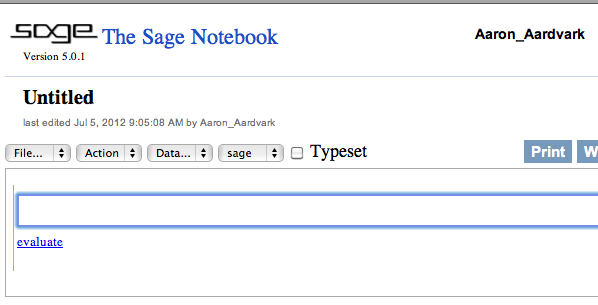

In any Sage worksheet, there are little boxes called input cells or code cells. They should be about the width of your browser.

Evaluating the content of an input cell is very easy.

First, click inside the cell so that the cell is active (i.e., has a bright blue border).

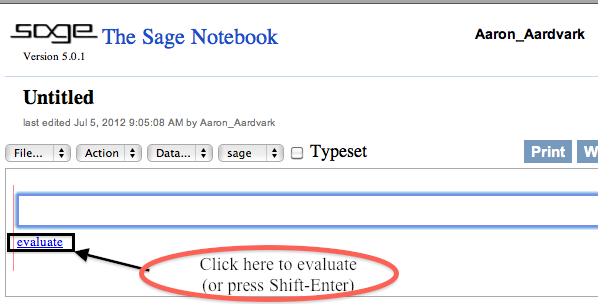

Then, just below the cell on the left, an “evaluate” link appears; clicking this link evaluates the cell.

If you are using the live version of this documentation, try evaluating the following cell.

sage: 2+2

4

Sage prints out its response just below the cell (that’s the 4

above, so Sage confirms that \(2+2=4\)). Note also that Sage has

automatically made the next cell active after you evaluated your first

cell.

You can also evaluate a cell using a keyboard shortcut.

- If a cell isn’t active (such as below, in the live documentation), click in it.

- Then hold down the Shift key while you press the Enter key.

We call this “Shift-Enter”. Try doing Shift-Enter with this cell.

sage: factor(2012)

2^2 * 503

An input cell isn’t much use if it can only do one thing, so you can edit a cell and evaluate it again. Just click inside, and then make any changes you wish by typing as usual.

Try changing the number 2012 above to 2011 and evaluate the cell

to find its factorization (surprised?); then try your own favorite

number.

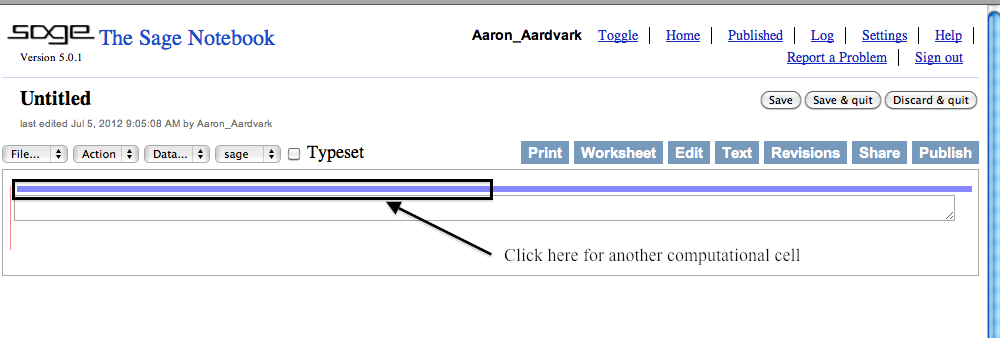

To do more math, we’ll need to be able to create new input cells. This is also easy.

- Move your cursor over the space above or below another cell.

- A blue horizontal line as wide as the browser should appear.

- Click on the line to insert a new cell.

If for some reason you need to remove or delete an input cell, just delete all the text inside of it, and then press backspace in the now-empty cell.

Try creating a few new input cells below, doing some arithmetic in those cells, and then deleting one of the input cells.

'Do some arithmetic in me, and make some other cells after me!'

Functions in Sage¶

To start out, let’s explore how to define and use functions in Sage.

For a typical mathematical function, it’s pretty straightforward to define it. Below, we define a function.

sage: f(x)=x^2

Since all we wanted was to create the function \(f(x)\), Sage just does this and doesn’t print anything out back to us.

We can check the definition by asking Sage what f(x) is:

sage: f(x)

x^2

If we just ask Sage what f is (as opposed to f(x)), Sage prints

out the standard mathematical notation for a function that maps a

variable \(x\) to the value \(x^2\) (with the “maps to” arrow

\(\mapsto\) as |-->).

sage: f

x |--> x^2

We can evaluate \(f\) at various values.

sage: f(3)

9

sage: f(3.1)

9.61000000000000

sage: f(31/10)

961/100

Notice that the output type changes depending on whether the input had a decimal; we’ll see that again below.

Naturally, we are not restricted to \(x\) as a variable. In the next cell, we define the function \(g(y)=2y-1\).

sage: g(y)=2*y-1

However, we need to make sure we do define a function if we use a new variable. In the next cell, we see what happens if we try to use a random input by itself.

sage: z^2

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

NameError: name 'z' is not defined

This is explained in some detail in following tutorials. At this point,

it suffices to know using the function notation (like g(y)) tells

Sage you are serious about y being a variable.

One can also do this with the var('z') notation below.

sage: var('z')

z

sage: z^2

z^2

This also demonstrates that we can put several commands in one cell, each on a separate line. The output of the last command (if any) is printed as the output of the cell.

Sage knows various common mathematical constants, like \(\pi\)

(pi) and \(e\).

sage: f(pi)

pi^2

sage: f(e^-1)

e^(-2)

In order to see a numeric approximation for an expression, just type the

expression inside the parentheses of N().

sage: N(f(pi))

9.86960440108936

Another option, often more useful in practice, is having the expression

immediately followed by .n() (note the dot).

sage: f(pi).n()

9.86960440108936

For now, we won’t go in great depth explaining the reasons behind this syntax, which may be new to you. For those who are interested, Sage often uses this type of syntax (known as “object-oriented”) because…

- Sage uses the Python programming language, which uses this syntax, ‘under the hood’, and

- Because it makes it easier to distinguish among

- The mathematical object,

- The thing you are doing to it, and

- Any ancillary arguments.

For example, the following numerically evaluates (n) the constant

\(\pi\) (pi) to twenty digits (digits=20).

sage: pi.n(digits=20)

3.1415926535897932385

Sage has lots of common mathematical functions built in, like

\(\sqrt{x}\) (sqrt(x)) and \(\ln(x)\) (ln(x) or

log(x)).

sage: log(3)

log(3)

Notice that there is no reason to numerically evaluate \(\log(3)\), so Sage keeps it symbolic. The same is true in the next cell - \(2\log(3)=\log(9)\), but there isn’t any reason to do that; after all, depending on what you want, \(\log(9)\) may be simpler or less simple than you need.

sage: log(3)+log(3)

2*log(3)

sage: log(3).n()

1.09861228866811

Notice again that Sage tries to respect the type of input as much as possible; adding the decimal tells Sage that we have approximate input and want a more approximate answer. (Full details are a little too complicated for this introduction.)

sage: log(3.)

1.09861228866811

sage: sqrt(2)

sqrt(2)

If we want this to look nicer, we can use the show command. We’ll

see more of this sort of thing below.

sage: show(sqrt(2))

sage: sqrt(2).n()

1.41421356237310

Do you remember what \(f\) does?

sage: f(sqrt(2))

2

We can also plot functions easily.

sage: plot(f, (x,-3,3))

Graphics object consisting of 1 graphics primitive

In another tutorial, we will go more in depth with plotting. Here, note that the preferred syntax has the variable and endpoints for the plotting domain in parentheses, separated by commas.

If you are feeling bold, plot the sqrt function in the next cell

between 0 and 100.

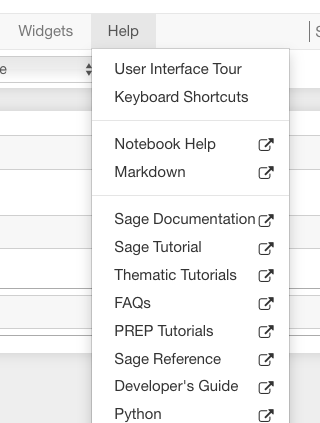

Help inside Sage¶

There are various ways to get help for doing things in Sage. Here are several common ways to get help as you are working in a Sage worksheet.

Documentation¶

Sage includes extensive documentation covering thousands of functions, with many examples, tutorials, and other helps.

- One way to access these is to click the “Help” link at the top right of any worksheet, then click your preferred option at the top of the help page.

- They are also available any time online at the Sage website, which has many other links, like video introductions.

- The Quick Reference cards are another useful tool once you get more familiar with Sage.

Our main focus in this tutorial, though, is help you can immediately access from within a worksheet, where you don’t have to do any of those things.

Tab completion¶

The most useful help available in the notebook is “tab completion”. The idea is that even if you aren’t one hundred percent sure of the name of a command, the first few letters should still be enough to help find it. Here’s an example.

- Suppose you want to do a specific type of plot - maybe a slope field plot - but aren’t quite sure what will do it.

- Still, it seems reasonable that the command might start with

pl. - Then one can type

plin an input cell, and then press the tab key to see all the commands that start with the letterspl.

Try tabbing after the pl in the following cell to see all the

commands that start with the letters pl. You should see that

plot_slope_field is one of them.

sage: pl

To pick one, just click on it; to stop viewing them, press the Escape/esc key.

You can also use this to see what you can do to an expression or mathematical object.

- Assuming your expression has a name, type it;

- Then type a period after it,

- Then press tab.

You will see a list pop up of all the things you can do to the expression.

To try this, evaluate the following cell, just to make sure \(f\) is defined.

sage: f(x)=x^2

Now put your cursor after the period and press your tab key.

sage: f.

Again, Escape should remove the list.

One of the things in that list above was integrate. Let’s try it.

sage: f.integrate(x)

x |--> 1/3*x^3

Finding documentation¶

Or, Why all the question marks?

In the previous example, you might have wondered why I needed to put

f.integrate(x) rather than just f.integrate(), by analogy with

sqrt(2).n().

To find out, there is another help tool one can use from right inside the notebook. Almost all documentation in Sage has extensive examples that can illustrate how to use the function.

- As with tab completion, type the expression, period, and the name of the function.

- Then type a question mark.

- Press tab or evaluate to see the documentation.

To see how this help works, move your cursor after the question mark below and press tab.

sage: f.integrate?

The examples illustrate that the syntax requires f.integrate(x) and

not just f.integrate(). (After all, the latter could be ambiguous

if several variables had already been defined).

To stop viewing the documentation after pressing tab, you can press the Escape key, just like with the completion of options.

If you would like the documentation to be visible longer-term, you can evaluate a command with the question mark (like below) to access the documentation, rather than just tabbing. Then it will stay there until you remove the input cell.

sage: binomial?

Try this with another function!

Finding the source¶

There is one more source of help you may find useful in the long run, though perhaps not immediately.

- One can use two question marks after a function name to pull up the documentation and the source code for the function.

- Again, to see this help, you can either evaluate a cell like below, or just move your cursor after the question mark and press tab.

The ability to see the code (the underlying instructions to the computer) is one of Sage’s great strengths. You can see all the code to everything .

This means:

- You can see what Sage is doing.

- Your curious students can see what is going on.

- And if you find a better way to do something, then you can see how to change it!

sage: binomial??

Annotating with Sage¶

Whether one uses Sage in the classroom or in research, it is usually helpful to describe to the reader what is being done, such as in the description you are now reading.

Jupyter Annotation¶

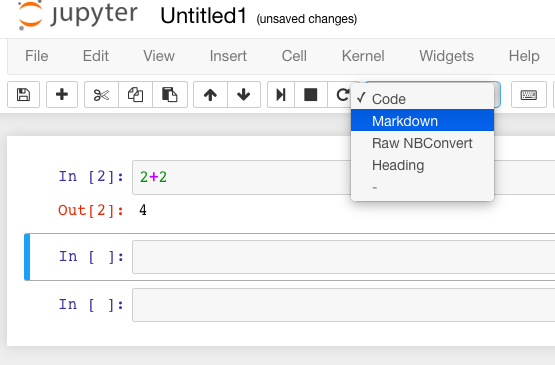

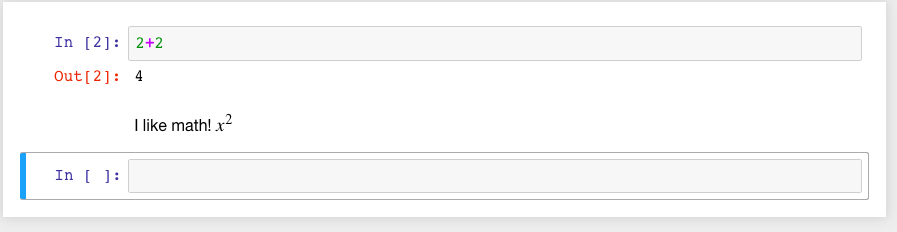

Thanks to a styling language called Markdown and the TeX rendering engine called MathJax, you can type much more in Sage than just Sage commands. This math-aware setup makes Sage perfect for annotating computations.

While the Jupyter notebook does not have as fully-featured a word processor as the SageNB, we can still do a fair amount. To use this functionality, we create a Markdown cell (as opposed to a input cell that contains Sage commands that Sage evaluates).

To do this without the keyboard shortcut, there is a menu for each cell; select “Markdown”.

Now you can type in whatever you want, including mathematics using LaTeX.

Then evaluate the cell (for instance, with “Shift-Enter”):

Markdown supports a fair amount of basic formatting, such as bold, underline, basic lists, and so forth.

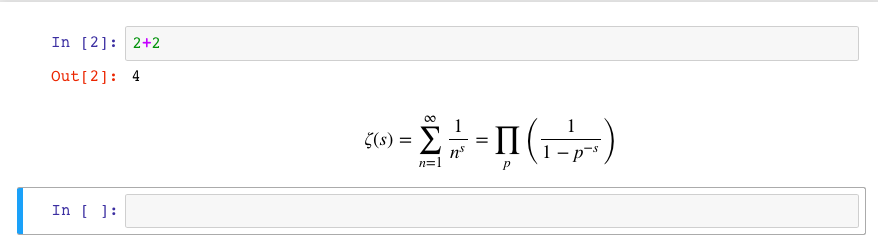

It can be fun to type in fairly complicated math, like this:

One just types things like:

$$\zeta(s)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n^s}=\prod_p \left(\frac{1}{1-p^{-s}}\right)$$

in a Markdown cell.

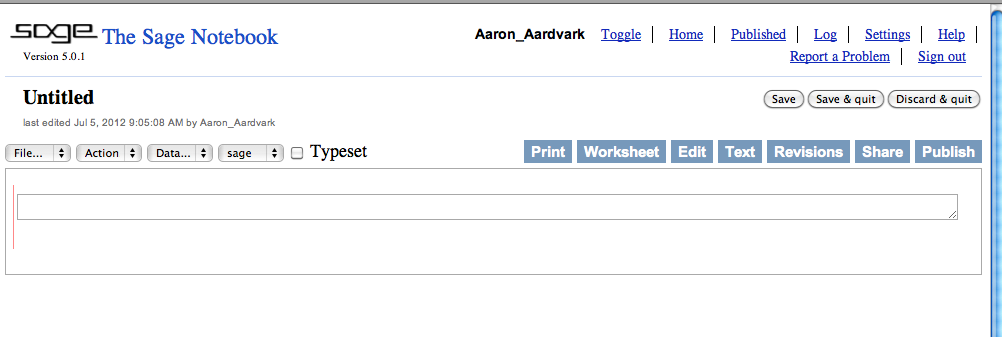

SageNB Annotation¶

Thanks to the mini-word processor TinyMCE and a TeX rendering engine called MathJax, you can type much more in the SageNB notebook worksheets than just Sage commands. This math-aware setup makes Sage perfect for annotating computations.

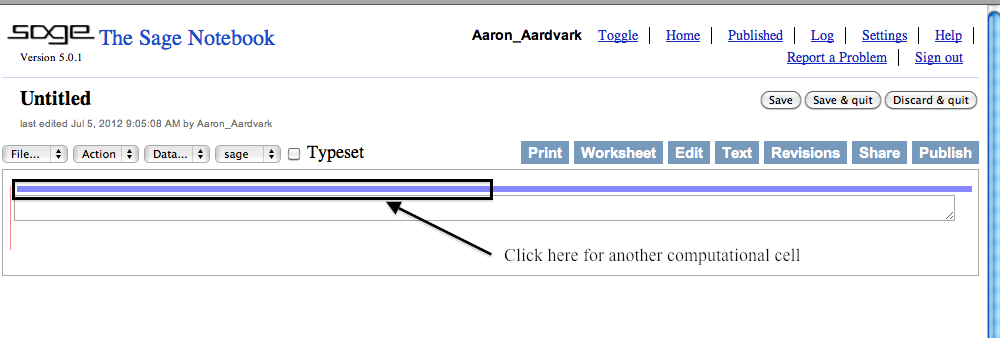

To use the word processor, we create a text cell (as opposed to a input cell that contains Sage commands that Sage evaluates).

To create a text cell, do the following.

First, move the cursor between two input cells, until the thin blue line appears.

Then hold the Shift key and click on the thin blue line.

So to create an input cell, one merely clicks, but one “Shift-Click”s to create a text cell. Here is what your text cell will look like.

In the live documentation, try inserting a text cell between the input cells below.

2+2

2+2

TinyMCE makes it easy for format text in many ways. Try experimenting with the usual bold button, underline button, different text fonts and colors, ordered and unordered lists, centering, and so on. Some of the shortcut keys you are familiar with from other word processors may also work, depending on your system.

There are two other things you can do which take advantage of the worksheet being on the web.

- It is easy to link to other helpful websites for additional information.

- While in the editor, highlight a word or two, and then click on the little chain link toward the bottom right of the buttons.

- You can now type in a web address to link to.

- Be sure to prepend

http://to the address. Normally, one should also select it to appear in a new window (so the Sage session isn’t interrupted if someone clicks on it).

- You may have already noticed that some of the descriptions above had typeset mathematics in them. In fact we can add nearly arbitrary LaTeX to our text cells!

For instance, it isn’t too hard to add things like

\[\zeta(s)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n^s}=\prod_p \left(\frac{1}{1-p^{-s}}\right)\; .\]One just types things like:

$$\zeta(s)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n^s}=\prod_p \left(\frac{1}{1-p^{-s}}\right)$$in the word processor.

Whether this shows up as nicely as possible depends on what fonts you have in your browser, but it should be legible.

More realistically, we might type

$f(x)=x^2$so that we remember that \(f(x)=x^2\) in this worksheet.

Here is a simpler example.

sage: f(x)=x^2

sage: f(9)

81

If \(f(x)=x^2\), then \(f(9)=81\).

It is simple to edit a text cell; simply double-click on the text.

If you are in the live version of this tutorial, try double-clicking on this text to edit this text cell (or any text cell) to see how we typed the mathematics!

Of course, one can do much more, since Sage can execute arbitrary commands in the Python programming language, as well as output nicely formatted HTML, and so on. If you have enough programming experience to do things like this, go for it!

sage: html("Sage is <a style='text-decoration:line-through'>somewhat</a> <b>really</b> cool! <p style='color:red'>(It even does HTML.)</p>")

Conclusion¶

This concludes the introductory tutorial. Our hope is that now you can try finding and using simple commands and functions in Sage. Remember, help is as close as the notebook, or at the Sage website.